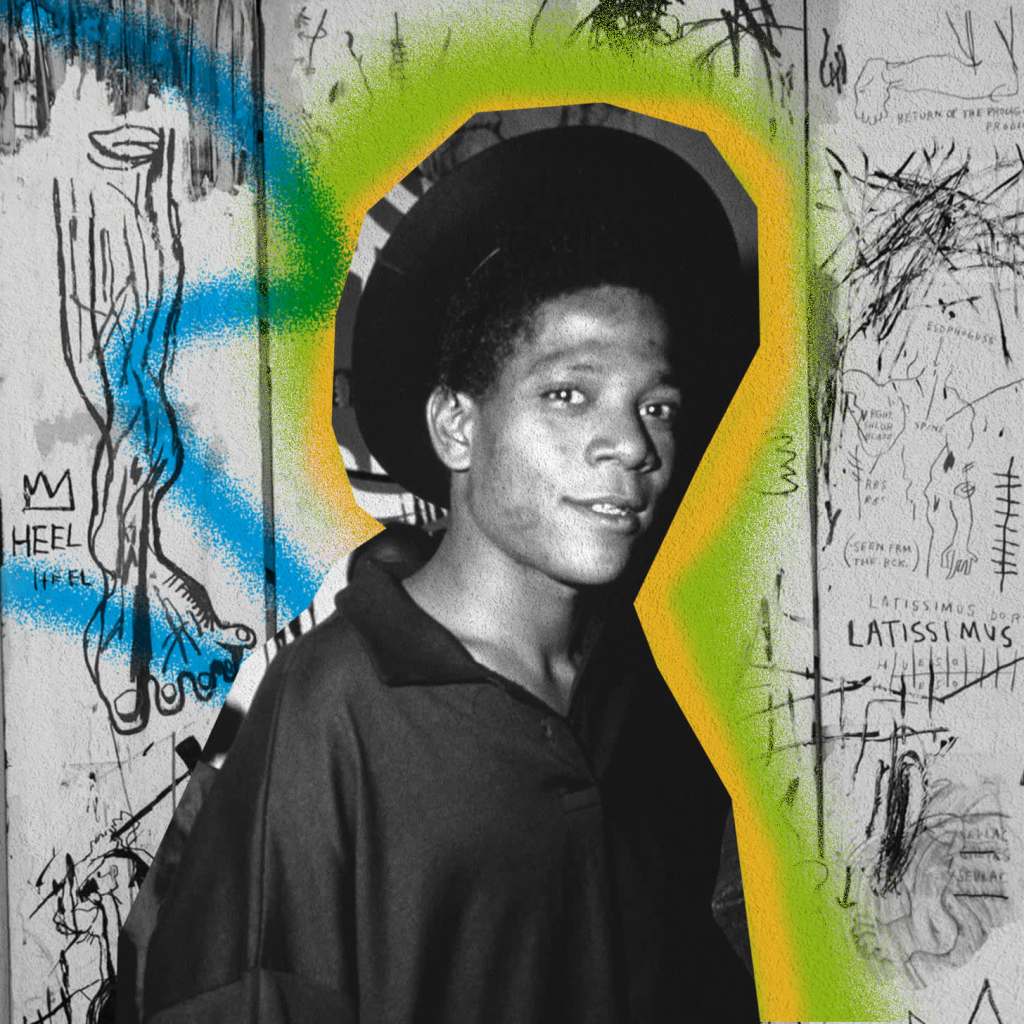

A look back at a 1983 Jean-Michel Basquiat interview forced me to once again consider Toni Morrison’s reverberating words. In “Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and Literary Imagination,” she argued that “a real or fabricated Africanist presence was crucial to their sense of Americanness.” “Their,” in this case, meant white literary authors. She posited that they distinguished themselves as a cohesive entity, while their identity and work hinged on the existence of a Black population kept in the shadows – historical integrity be damned.

Morrison’s argument can be extended to the world of visual art and, more specifically, to Basquiat’s presence in NYC’s “neo-expressionist” art movement of the late ’70s and early ’80s. A year after his 1988 death, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) was offered Basquiat’s work, and the organisation declined. Then-Head Curator Ann Temkin contended that his paintings were not marketable. “I didn’t recognise it as great, it didn’t look like anything I knew.” By 1992, the Whitney Museum debuted its Basquiat retrospective exhibition; it was the first occasion in which the artist – who died by heroin overdose at age 27 – would have his art over the years studied by an American institution.

“It’s not lost on me that the celebration of Basquiat’s genius was rising as he met his fate in dying young, adding to a long line of Black men who never made it to 30 but were revered posthumously,” Amy Andrieux, executive director and chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA), tells POPSUGAR. “Always late to the Black familiar, the white gaze continues to love us in a vicious cycle of anti-Blackness to anti-Blackness; from ghetto until proven fashionable.”

A slew of rather racist questions made it clear that art historian Marc H. Miller (then an adjunct professor at New York University) did not find Basquiat “fashionable” in 1983. He called the young artist “primal” in his artistic approach, to which Basquiat responded, “You mean like an ape?”

“The celebration of Basquiat’s genius was rising as he met his fate in dying young, adding to a long line of Black men who never made it to 30 but were revered posthumously.” – Amy Andrieux

Miller demanded that Basquiat explain every bone, stroke, and scratch, reducing his process to arbitrary and alogical thinking. He wasn’t the first to project this appraisal, either; the artist himself talked about being relegated to a “wild monkey man.” Early patrons wanted Basquiat’s colour schemes to make sense to them. His erratic arrangements were often compared to the more legible placements of artists like Leonardo da Vinci – whom Basquiat curiously named a favorite.

Halfway through his exchange with Miller, Basquiat’s patience ran thin. He worked up the wit to return a fraction of the offensiveness by talking with a mouth full of food. A cursory survey of the YouTube video’s comments section further corroborates Morrison’s words. Several reactions laud Basquiat for having no rhyme or reason to his work and being an artist whose expressions were devoid of any cultural or political messaging.

Yet any Black, historically informed person looking at the larger part of Basquiat’s canvases can see this is a lie. He was informed by being a Haitian Puerto Rican from Brooklyn, in a gritty era later defined by the crack epidemic, the rallying cries of the Black Panthers and Young Lords, and the blossoming of hip-hop from subculture to mainstream.

“NYC had been and would continue to be a hot pot bubbling with creativity,” Andrieux tells POPSUGAR. “Straddling the dreams of the haves and the have-nots, landlocked between lore and possibility, this was a city of yellow cabs and hotdog stands, of syncopated imagination and improvisation as a means of survival for its Black and brown bodies.”

A result of academia’s racist dogma that says white men are the keepers of intelligentsia, Miller arrogantly tries to sell Basquiat on what is avant-garde, overlooking his pro-Black, pro-immigrant, anticapitalist language and imagery, often delivered in Spanish. An example stands out in Basquiat’s “Obnoxious Liberals,” which features the political statement, “Not for sale.” But to the Millers of the world, Basquiat was Black, unlettered, and disenfranchised, and therefore not as smart or capable as the likes of Robert Rauschenberg or contemporaries like Keith Haring.

Basquiat explained that a large part of his canvas works were collages of working drafts, with layers continuously added on and taken away, creating complementary and juxtaposed pieces by design. He expressed that his art was inspired by his personal experiences and things he witnessed, be it on television or in American society. Bottom line: the genius of Basquiat’s work duplicates no one, and much of it conjures images of Black history in relation to the United States.

Writer Greg Tate’s famous 1989 analysis of Basquiat, Black visual artists, and the Western canon also still resonates today: “It is easier for a rich white man to enter the kingdom of heaven than for a Black abstract and/or conceptual artist to get a one-woman show in lower Manhattan, or a feature in the pages of Artforum, Art in America, or The Village Voice. The prospect that such an artist could become a bona fide art-world celebrity (and at the beginning of her career no less) was, until the advent of Jean-Michel Basquiat, something of a f*cking joke.”

Basquiat was an artist ruled by instinct, with a predisposition to act on impulse and intuition. Commonly forgotten, he began as a writer under the graffiti alias SAMO, alongside the encouragement of childhood friend Al Diaz. A genesis pillar of hip-hop culture, graffiti possessed a singular objective of fame: plastering one’s tag anywhere and everywhere. Basquiat, however, employed the practice as a means to share language-oriented messaging or oblique pieces of poetry (origin of cotton; a conglomerate of dormant genius; a pin drops like a pungent odor; life is confusing at this point; for the so called avant garde). But he was not, as some have suggested in the past, all that interested in money and fame. He was more interested in being considered among art’s European “forefathers.”

He was informed by being a Haitian Puerto Rican from Brooklyn, in a gritty era later defined by the crack epidemic, the rallying cries of the Black Panthers and Young Lords, and the blossoming of hip-hop from subculture to mainstream.

Once dismissed as simpleminded and overhyped, Basquiat and his incomparable oeuvre emerged as a central subject at the Whitney, after pressure mounted to ignite a new and visionary exhibition program. “Somewhere along this journey to so-called equality, the voice and platform of Black artists diminish as their culture cachet is co-opted, commercialised, acquired on trend and at a bargain (if at all!), and then relegated to the dark crevices of storage houses,” Andrieux says.

As part of the 2021 launch of the “About Love” campaign by Tiffany & Co., fronted by everyone’s favorite Black capitalists Beyoncé and JAY-Z (the Carters are known Basquiat collectors), the luxury jewelry retailer utilised Basquiat’s 1982 painting “Equals Pi,” creating a holiday-themed, limited-edition advertisement. We don’t know that Basquiat would ever have collaborated with a brand such as this one, but we do know that the art co-opted for this campaign was not, as previously suggested, any kind of “color-specific” homage to Tiffany & Co’s robin’s-egg blue.

The retailer’s Executive Vice pPresident Alexandre Arnault implied that Basquiat produced work in the brand’s honour. Yet Vanity Fair noted that “Equals Pi” was painted in 1982 and that the artist didn’t cross paths with Tiffany “until 1985 when he traveled with Tony Chow of Mr. Chow to Hong Kong to attend a Tiffany-hosted dinner.” Chow stated, “I don’t think [Basquiat] liked my host very much. He was very rebellious, and so ordered the most expensive wine, you know, it was outrageous, this bottle of wine!”

Decades later, this once-misunderstood Brooklyn boy of profound wisdom and agency, whose work was “unrefined” and “unexplainable,” is now regarded as a singular genius by the very institutions that rejected him. But there was the art world before Basquiat, and there was the art world after him – his detractors and champions were never the same again.