I’ve never been good with criticism – giving or receiving it. My therapist might reason it’s due to being a “recovering codependent,” a phrase I like because it sounds like an addiction to people-pleasing, rather than a moral failure. So when I picked up “Who Is Wellness For?”, Fariha Róisín’s memoir and deep dive into wellness culture, with the intention of reviewing the book, I was understandably apprehensive about my abilities to act the critic. I asked my friend, an excellent movie reviewer, for advice, and he urged me to try to embody the stereotype of the snobby critic, with a cigarette in one hand and a latte in the other. Act the part, and the thinking will follow, etc. So I tried it: I made a cup of black coffee and set it up in front of my laptop with a prerolled joint I bought from a couple at a queer pool party. But the hot mug and smoke only made me sweat and blink more.

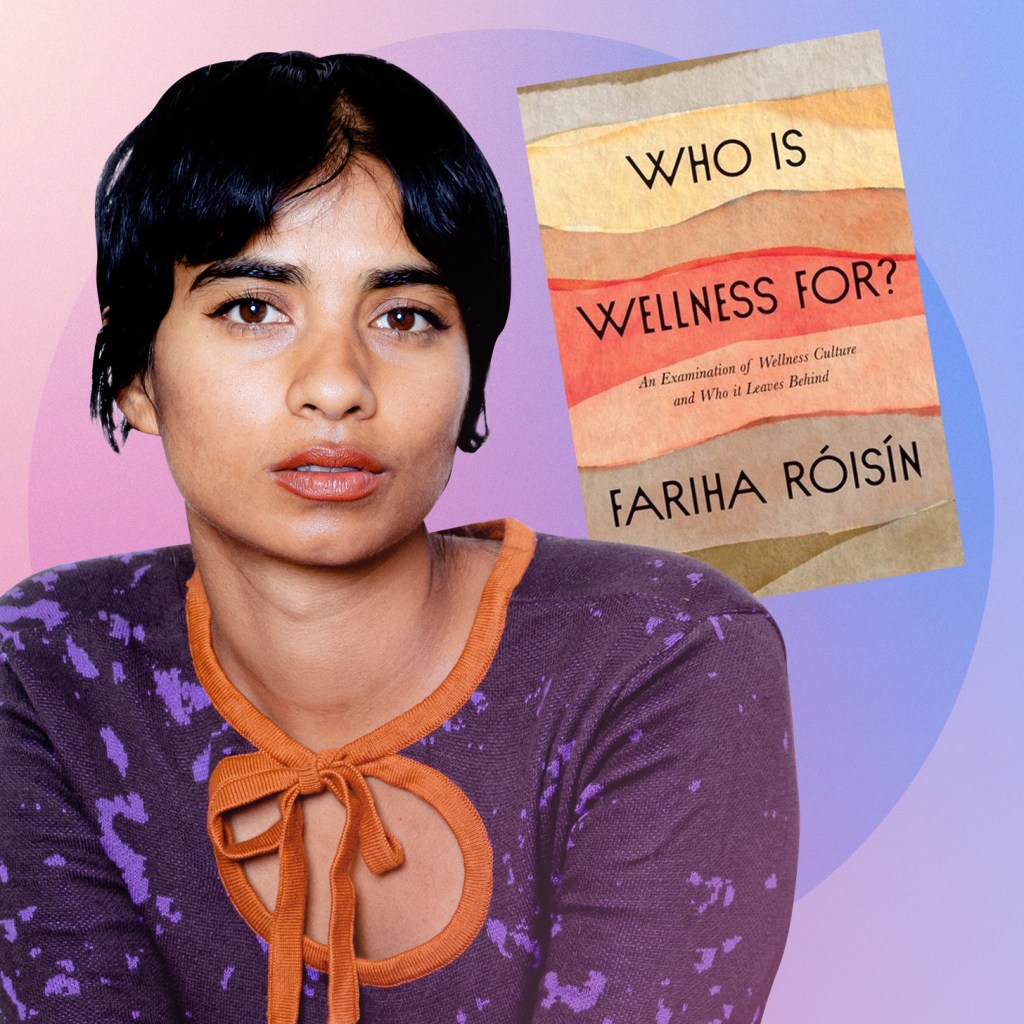

So, instead, I wrote a love letter – mostly because I love this book and also because I love Fariha Róisín. A poet, novelist, journalist, and teacher, she dedicates her career to examining wellness through a social justice lens in an effort to bring self-care to all. She has a cool-girl aesthetic that can only work if you’re not trying too hard. She’s an artist fit for worship, yet her humanity is what draws in her audience.

I originally discovered Róisín through her newsletter “How to Cure a Ghost,” where I stumbled upon an advertisement for her class “Writing with Vulnerability in Mind.” Until then, I had always considered vulnerability more of a weakness than a strength. At 22, I was diagnosed with complex post-traumatic stress disorder and had spent years spiralling within trauma therapy. Róisín was the first person I told.

The book might make people feel many things – but that’s the beauty of Róisín’s writing style. Just because something is well-researched and thick with psychological definitions, doesn’t mean it can’t read like poetry.

In my application for the class, I wrote, “I have been desperate to get back in touch with my emotions through the medium of writing.” And she replied, “I’m sorry about your PTSD, but I, as someone who has a lot of childhood PTSD, understand. I’m here to talk about that more, and I’m grateful for you naming this and wanting to look more deeply at it.” She makes me feel seen, not just in her work but also in this kinship – an acknowledgment that we live in the same space of limbo into which those still grappling with trauma are thrust.

I joined her class, along with a cohort of about 20 of us who gathered online. It was early in the pandemic, when Zoom still felt like a portal where other parts of the world could join in one room – people from the US, India, Germany, Indonesia, and the Netherlands logged on. Until then, I had taken various classes on the craft of writing, but this was different – her deeply held belief that she was put on this earth to help others permitted us to be earnest.

It was a unique experience for me, surrounded by people who spoke sincerely about how trauma isolates you. They each understood the unique form of suffering when capitalism feeds off your pain. It was also a pleasure to learn from Róisín, not just about opening up but as a writer, because she is simply so damn talented.

So, when Róisín published “Who is Wellness For?: An Examination of Wellness Culture and Who It Leaves Behind” this summer, on the ironies of the wellness industry, I reached out to talk with her about it. Ahead is what transpired between us.

“I never felt my goodness as a child. I was literally crying about that this morning actually,” Fariha Róisín says to me over the phone. It’s a Wednesday, and as I pace my apartment in New York, Róisín is across the country, ordering a matcha latte with oat milk. I listen to the whir of an espresso machine in the background at the LA cafe she’s stopped at before her next reading event. Her milk preference reminds me of a chapter in “Who is Wellness For?” about living with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), a chronic illness that her parents ignored during childhood that often led to severe pain – just one of many forms of neglect that Róisín experienced growing up.

Róisín says she didn’t meet many people with childhoods like her – her mother was violent and sexually abusive, and her father looked the other way. “I had a very exceptionally painful childhood in that sense,” Róisín says. “A good childhood is a privilege,” Róisín writes. “The way we downplay this reality results in collective gaslighting . . . Despite the odds against us, children of neglect remain forced to live normal lives. to get on with it.”

Her interest in wellness was piqued at a young age with the onset of her IBS and was renewed later on as an adult, when she was diagnosed with childhood PTSD. In the overlap of these chronic illnesses, Róisín noticed a connection between trauma on a personal, cultural, and global level: how childhood abuse can give you IBS, how imperialism and colonialism strip millions of their health and well-being, and how our lack of caring leads to a dying planet.

In her novel published in fall 2020, “Like a Bird,” I saw myself in the protagonist’s desire for community, love, and safety, which are desires that Róisín explores more deeply in her new book. The multidisciplinary artist blended memoir and journalism to tackle the multibillion-dollar wellness industry and how it impacted her individually and systemically. “Who Is Wellness For?” examines the commodification and appropriation of wellness through the lens of social justice, providing resources to help anyone participate in self-care.

And she calls out how the current wellness industry that aims to “heal” is incredibly violent. “Over 450 million Indians live under the poverty line, yet wellness – particularly yoga – is a multi-billion-dollar industry extracted from our culture,” she says. “The British outlawed yoga for Indians when they took over. But when there was a rebirth in Hinduism – it was sanitized for a western audience.” It all comes back to profit: who gets to be well and who gets to have wealth. “My book will make many people mad,” she adds proudly.

The book might make people feel many things, not just anger – but that’s the beauty of her writing style. Just because something is well-researched and thick with psychological definitions doesn’t mean it can’t read like poetry. For comparison, trauma therapist Resmaa Menakem defines traumatic retention as, “A trauma-related behavior that gets passed down through the generations until it loses its original context and begins to look like culture.” In the book, Róisín writes:

“Retention reminds me of bloating when you are puffy with water or food, the feeling of immovability, the stuckness of unmetabolized trauma.”

It’s visual and tactile. She continues, “But how, I began to ask myself, can we expect the body to metabolize toxicity at this level?” In other words, how do we process something much larger than the individual experience, like generational trauma?

Navigating life as a queer Muslim Bangladeshi from an abusive background, Róisín says writing is what saved her. “Even when punished, I was still a good kid. Moving through my 20s, I started to work toward healing,” Róisín says. “Sharing that story felt important, and I encourage people to feel like they have the permission and social responsibility to write their story.”

Róisín admits she didn’t anticipate writing the book would be so cathartic. “I didn’t go to the page with all the answers, so it led me to surrender completely to the book.” Typically, memoirs are written with a narrative distance. Yet “Who is Wellness For?” reads like you are journeying with Róisín as she investigates the physiology of trauma while processing her own – allowing the tone to feel raw and intimate. As a reader, when she writes, “I am my own litmus test for evolving in real-time,” I find myself wanting to evolve along with her as I finish each of the book’s four main sections: mind, body, self-care, and justice.

A discussion of justice doesn’t seem out of place in a book about wellness; Róisín believes caring is revolutionary. “We’re here because we don’t care for anything,” Róisín says, referring to how society contributes to the environmental apocalypse, patriarchy, white supremacy, and all the other world injustices. “White supremacy is the belief that you don’t have to care – I mean, why care when you can just steal it [through colonialism and imperialism]?” Violence or anything reactionary rarely comes from caring too much, Róisín points out. “People turn against each other when they feel uncared for,” she says. “I’m aware of what that does to a person. True love from an adult caretaker is a miracle. I know because I never received it.”

Róisín takes the global problem of “lack of care” and gives us an individual lens through which to view it, arguing that if we want true wellness for ourselves, we must shift towards a “nurturance culture,” which is an investment in everyone’s well-being. Care, in all the many ways you can define it, is the root of the book: the care Róisín wanted from her parents, the lack of care we have for the planet, and how our patriarchal society views caretaking as feminine, therefore undervaluing it. But more than care – or at least, more than self-care – is the lack of practice we have with empathy.

Self-care is often encouraged in the wellness industry. But Róisín writes that “prioritizing self-optimization at the expense of community wellness” is capitalism’s design. There’s nothing inherently wrong with prioritizing your health and needs. But it’s worth questioning why we participate in harmful environmental practices for the sake of “glowy” skin, for example. Or, more directly: how “wellness culture has become a luxury good built on the wisdom of Black, brown, and Indigenous people while ignoring and excluding them.”

So, how do we get out of this cycle? Róisín says the first step is involving yourself in local communities – volunteering at shelters or tending to the land at community gardens. But from there, it comes down to you as an individual. “I think there’s an obsession with being told what to do,” Róisín says. “True social action is cultivated from a genuine place of care rather than fear of judgment.” All you can be is truthful and honest with your community.

As I look out my window at the bustling street below, I picture Róisín working with her hands in the community garden near her old place in Brooklyn. She recently moved to LA, after struggling with a mice infestation, which “felt like a sign to move on,” she says. So much of healing is the ability to move forward – not necessarily to “let go,” but to develop an acceptance of what happened, so you can continue to evolve.

Before I hang up, I ask one more question: “So, who is wellness for?” As Róisín goes along with her day on the other side of the phone, I hear a smile form. “Wellness means for all,” she says – regardless of race, identity, socioeconomic status, or able-bodiedness. “It’s for everyone.”