Image Source: Denzel Golatt

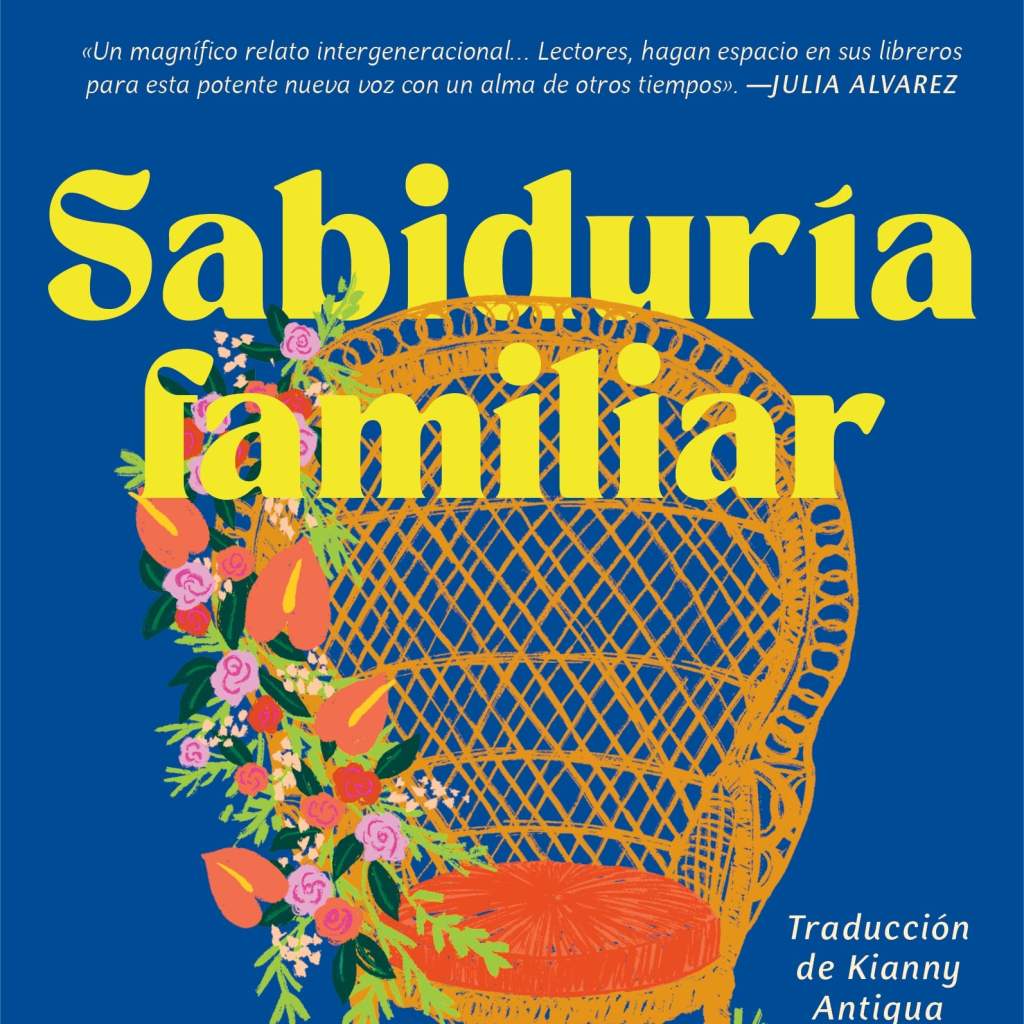

New York Times bestselling author Elizabeth Acevedo, known for her award-winning YA novels, recently published her first novel for adults. “Family Lore,” and its Spanish translation, “Sabiduría Familiar,” is a magical intergenerational tale loosely inspired by Acevedo’s mother and tías that touches on family, love, and grief.

Related: Julissa Calderon Launched the Second Edition of Her Dream and Manifest Journal Collection

The novel features multiple points of view from members of the Marte family. There’s Ona, who possesses a magical alpha vagina but can’t seem to bear children. Pastora is the reader of people’s truths who desperately wants to solve her siblings’ problems. Matilde is kindness incarnate but has spent her entire marriage covering up her husband’s infidelity. Flor is the seer who can predict when someone will die; she suddenly decides to host a living wake for herself and refuses to tell her sisters – Matilde, Pastora, and Camila – the motive behind the unexpected celebration. Something awakens among the women, and spanning the three days prior to the wake, the Marte family unravel secrets from the past and present, face undeniable truths, and reckon with trauma and shame, all while navigating grief and loss.

POPSUGAR caught up with Acevedo to discuss her new novel, which centers a Dominican American family through the voices of the Marte women. This poignant novel is unlike anything you’ve read this year, as it is equal parts harrowing and laugh-out-loud funny.

Image Source: HarperCollins Publishers

POPSUGAR: Why did you decide to write a novel for adults?

Elizabeth Acevedo: I think the impetus for an adult novel was less of my making a decision to write for adults, and more that the story made it very clear that I would be stretching in terms of language and content. And the audience would need to have a certain level of experience to bring to the text. It’s also going to be published in Spanish. What’s the importance of telling our stories in dual language? Especially when we don’t get to see many of our stories translated. Writing intergenerational stories is so important to me, and I think having my work translated allows for those stories to be read intergenerationally by a larger audience of people. I love picturing nieces and aunts, mothers, daughters, and cousins who wield different languages on a daily basis, sitting around discussing this book bilingually.

PS: What was it like fictionalizing your family’s history? What research did you do? Who from your life inspired some of these characters?

EA: I would say that some of the text is taken from family history and fictionalized, but the majority of the novel is wholly imagined. The only person I actively interviewed was my mother. I did take a research trip to the Dominican Republic with my mother and two of her sisters. We traveled to the rural township where they’d been born and raised. Listening and watching them on that trip was so helpful as I worked on the cadence, energy, and verve of writing the Marte women.

PS: On “Good Morning America,” you mentioned that you write to interrogate love – “love as a practice, and not love as a feeling,” and I love that. What is your practice for love? How has it changed, if at all, with you now as a mother? How do you practice self-love, and how are you juggling and prioritizing motherhood and writing?

EA: A lot of my scholarship on love has been through reading bell hooks and her contemporaries. It’s made me reimagine how one loves themselves and how care and love are often conflated. I practice self-love by allowing a lot of grace. Something I struggled to do for a long time. Motherhood has taught me I literally cannot be everything for everyone. I can only do my best, ask for help, sleep the few hours the baby lets me sleep, and wake up the next day to try again. When the baby was first born I set aside four months where I was wholly committed to parenting, and then slowly I reintegrated back into work and writing. But it’s still a process to learn how to make art and also raise a little one.

PS: How do the characters in “Family Lore” practice and prioritize self-care and love?

EA: Each character in “Family Lore” gives an individual answer to this. Pastora practices self-love by never leaving something unsaid. Matilde dances. Ona and Yadi go to therapy and try to find language for what hurts them. I think the various answers on love can be found in the flashbacks and the ways they had to advance beyond smallness.

PS: You’re known for writing about women, matriarchs, mothers, and daughters. And you do it so well. Reading each of these women, readers can easily see themselves or their mothers, sisters, and friends. But there were also moments reading about the experiences of Flor, Yadi, and so forth where one can wonder about some of the secrets that might exist in their own families. Why was it important for you to use the tools of flashbacks and reflections as a lens for these women to heal and reckon with the things that have happened in their lives?

EA: I think for those of us who come from families where silent enduring is a central virtue, it can mean we haven’t seen healing modeled. We’ve only seen restraint and disembodiment and survival. The structure of the novel “Family Lore,” which toggles back and forth in time, lets light into the silence. And since one of the conceits is that these flashbacks and stories are being told to the narrator, then we know that we are reading and actively struggling against silence. We watch the women learn in varying degrees to let each other in.

PS: What is the importance of oral storytelling and of oral history?

EA: For many of us, we may come from families that have only recently acquired literacy on a mass scale. And so many of the stories of our families have been passed down orally. Many of the stories of our homelands and islands and ancestry have been passed down orally. There’s a preservation that can be lost if those stories don’t continue being told. If they aren’t held in the same regards as the most important tomes. Magical realism plays a major theme in the book, but for most Latine and Caribbean people like myself, these spiritual gifts are very much real and usually manifest within the women of the family.

PS: Why was it important for you to weave spirituality into “Family Lore” in this way?

EA: Precisely for that reason! For those of us who just know magic, who were raised with it as a spiritual system, as a system that works alongside how we live. I think magical realism as a subgenre of literary fiction is all about resistance, and I wanted to lean into how magic allows for people and characters to believe innately that they are necessary and additive to their families and communities. The premise that kick-starts the novel is a living wake for Flor, forcing the matriarchs and women to reckon with past events, traumatic experiences, grief, death, and more. In a way, this sets the sisters and the family up to make peace with the things they had or were forced to let go.

PS: What is your family lore? Do you have magic or gifts like any of the characters in your book?

EA: Oh, I wish! My mother often has dreams that come true. So, I’ll say she definitely has a gift. And I wish all vagina-having people an alpha vagina, but I can’t say I have many gifts like the women in the novel. I might be more like Matilde, I cobbled my own gift together out of love and practice.

PS: Lastly, what has changed for you since becoming a mother and a renowned writer?

EA: For a long time, I’ve been working to slow down. I don’t work in a corporate world and yet I was ingrained in similar rat races. That’s not how art is made. Art needs one to live and think and walk and live some more. It’s always humming under the skin, and if one sees the world as an artist then there isn’t anything to chase. The art is always waiting. And that permission to be present as a mother, and partner, and person, and the art would only benefit from that adherence to paying attention, has been drilled home by the gift of my son.