- POPSUGAR Australia

- Beauty

- Why “Blackfishing” Is So Common Among White Influencers – and Why It Needs to Stop

Why “Blackfishing” Is So Common Among White Influencers – and Why It Needs to Stop

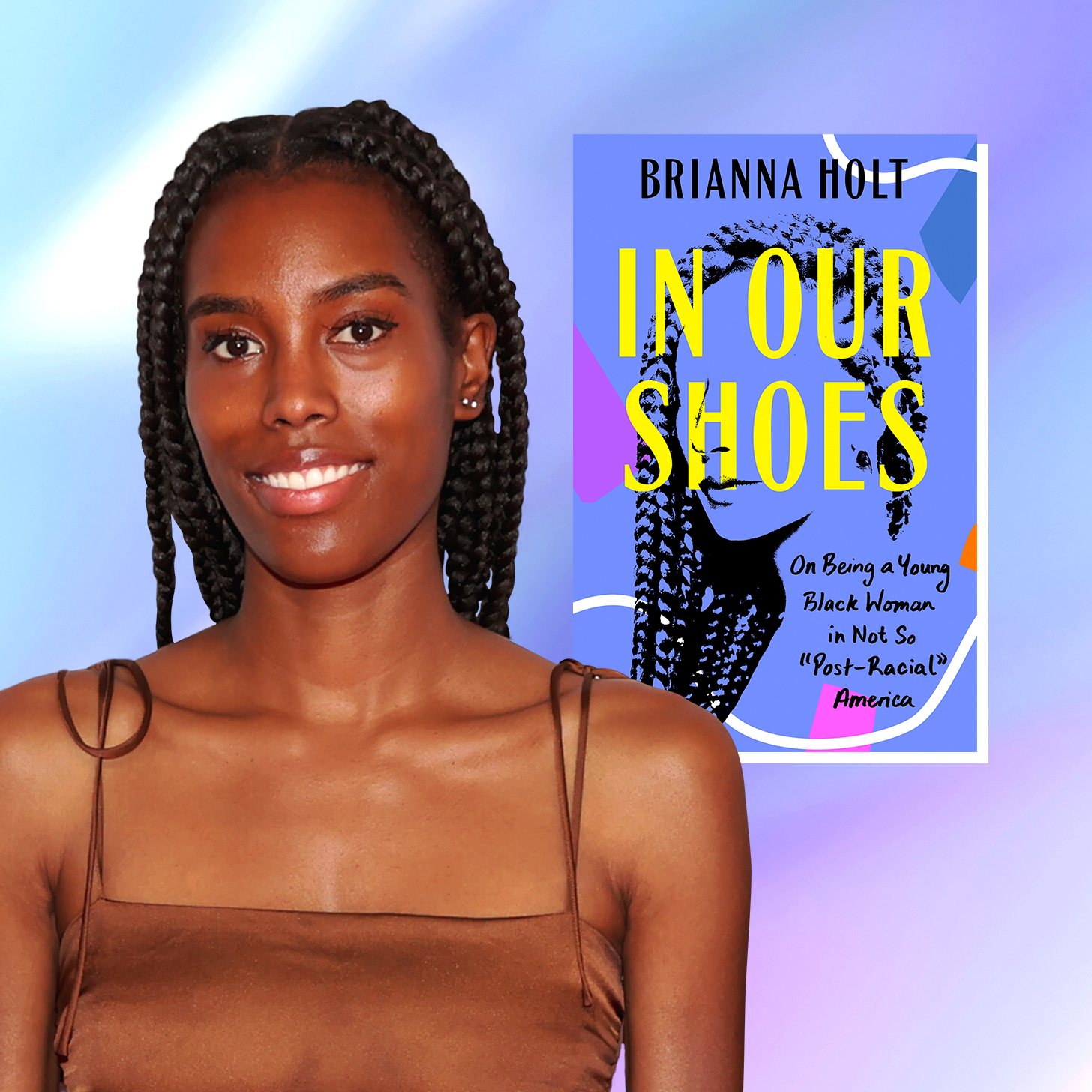

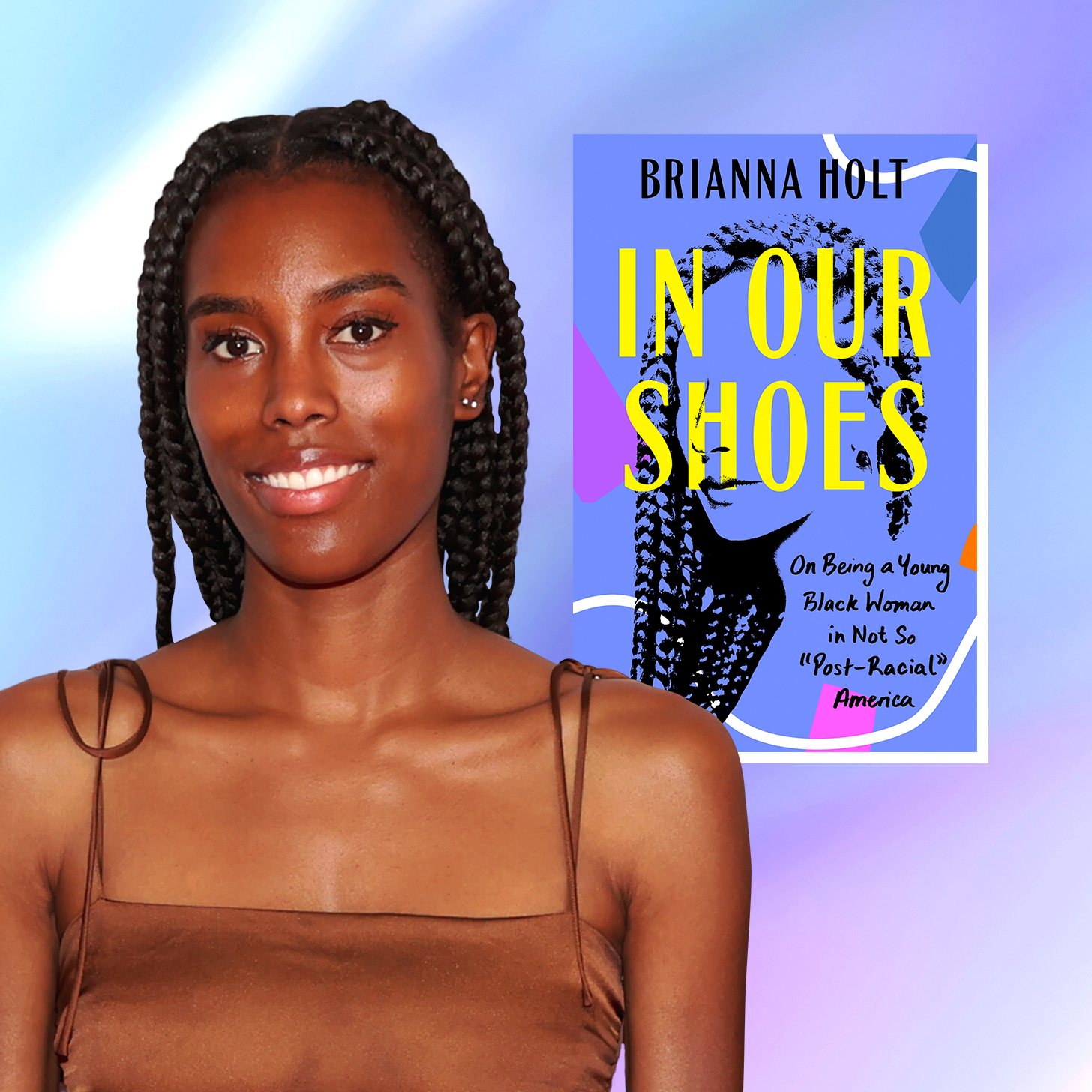

You’ve likely seen Brianna Holt’s name printed somewhere; she is a well-known journalist who has covered identity, race, and culture for outlets like The New York Times, The Cut, and others. In her new memoir – “In Our Shoes: On Being a Young Black Woman in Not-So ‘Post-Racial’ America,” on sale on April 11 – she explores these topics in even greater depth.

In this excerpt, Holt describes the phenomenon of “blackfishing” – when non-Black women attempt to present themselves with a Black or mixed-race appearance. It’s an important reminder of the ways in which Black beauty, culture, and trends are continuously co-opted, and a call to action to hold people who partake in this appropriation accountable.

Since the rise of Instagram, a new form of physical cultural appropriation has grown in popularity among non-Black women who make cosmetic alterations or edit their photos in ways that present themselves as less European-looking, racially ambiguous, or of mixed ancestry. The phenomenon has a name: blackfishing. Coined in 2018 by journalist Wanna Thompson after she realized a new wave of white women was cosplaying as Black women on social media, blackfishing describes someone who is accused of pretending to be Black on social media by using makeup, hair products, and in some cases surgery to drastically alter their appearance to achieve a Black or mixed-race look. With the additions of deep self-tanner and filler-injected lips, coupled with manipulated hairstyles and wigs, and sometimes surgery to widen the hips or enlarge the butt, the previous look of white women with naturally pale skin, classic European facial features, thin bodies, and straight hair has transformed into a look that appears mixed-raced of some sort. Some Instagram influencers, like Swedish model Emma Hallberg, @emmahallberg (who is infamous for being the first documented example of the practice of blackfishing), have been able to fool their fans, white and Black, into believing they are not white. Meanwhile, some non-Black celebrities, like Kylie Jenner and Ariana Grande, have quietly adopted the look, causing some fans to associate their sudden change in features with puberty as opposed to some of the alterations found in blackfishing.

Related: These Women Inspired the Trends You Love, From Y2K Style to Maximalist Nails

Thompson blames access through the media. In an article for Paper magazine, she writes, “White women have been able to steal looks and styles from Black women, more specifically styles that Black women in lower-economic communities have pioneered. With the help of the media, white women have been credited profusely for creating several ‘trends’ that have existed long before they discovered them. What makes this ‘phenomenon’ alarming is that these women have the luxury of selecting which aspects they want to emulate without fully dealing with the consequences of Blackness.”

So long as people appropriate us, we have the right to point it out.

Whether someone goes as far as lying about their race, or undergoes cosmetic procedures and adopts certain expressions to pass as non-white, the portrayal capitalizes off the “exotic” looks of historically oppressed minorities. Most women who take part in blackfishing are in denial, and maybe that’s because, unlike historical blackface performers, the perpetrators are not performing it with the explicit intention of mocking and ridiculing Black people; nevertheless, it is exploitative and wrong. Not only that, but it actively takes away representation and opportunities from Black women. It also encourages fetishism of another person’s appearance, so much that the blackfishing person is willing to go to great lengths to adopt the appearance themselves. In the same way some non-Black men have been known to fetishize Black women, some of their female counterparts are doing the same through their appropriation of their looks and expression. The only difference is that the fetishism is not romantic or sexual, nor nearly as verbally explicit, but it is present in their cosmetic decisions and style choices. Fetishism is to have an excessive and irrational commitment to or obsession with something or someone. And when non-Black women are so heavily influenced by Black women’s expression, word choices, articulation, clothing sense, hairstyles, and physical attributes – a phenomenon that is rarely a two-way street – obsession is the only explanation. Picking which parts of Black women they want to copy, and not dealing with the negative experiences that come with actually being a Black woman online or in real life, suggests that some women view Blackness as lucrative.

Related: The Mielle Rosemary Oil Controversy Points to a Bigger Issue

Furthermore, their gain is through social media, where these same white women have been credited abundantly for starting trends that were pioneered mostly by young Black women with fewer resources. As Thompson laid out so eloquently for Paper magazine, “What makes this both so harmful and insulting is that Black women have to work twice as hard to obtain the same, if not fewer, benefits as white women in these spaces, so when white influencers are rewarded with partnerships and brand sponsorships under the pernicious guise that they are racially ambiguous women, it’s beyond infuriating.” The same Black aesthetic that some white and non-Black women try to emulate is an aesthetic that many dark-skinned Black women are still shunned for having all on their own, like rarely being represented in the media for having dark skin while watching white women become more desirable from darkening their skin. What these women fail to realize is that they want access to Blackness but don’t want the suffering that comes along with it and don’t even have the consciousness to acknowledge how Blackness has molded so much of their aesthetic. Frustratingly, so many of these celebrities and everyday women appear silent or do the bare minimum when issues of racial injustice occur, suggesting they strive to emulate only these women’s aesthetic, but not their values. Whether or not their participation in blackfishing and cultural appropriation is done with ill intent, they want to receive accolades and privileges for appearing racially ambiguous and holding street knowledge while remaining socially, politically, and constitutionally white.

When Black women bring up these frustrations, with women co-opting our existence and benefiting from it in ways we don’t benefit ourselves, we are often perceived as jealous or bitter. To this, I respond, is it surprising at all that a marginalized group is frustrated by seeing white women who already have a social and cultural advantage be rewarded for appropriating features that marginalized groups are routinely ridiculed or passed on for? I don’t think any Black women are jealous of women who try to look like Black women, but instead are pissed off by the social, cultural, and financial ease that comes with being a white person partaking in blackfishing, especially on the internet. So long as people appropriate us, we have the right to point it out.

Read More POPSUGAR Beauty

- These Vitamin C Products Are the Secret to Glowy Skin

- What to Know Before Trying the Copper Hair Colour Trend

- These 13 Lipsticks Are the Perfect Dupe for Charlotte Tilbury’s Pillow Talk

- Slay Or Nay: The Viral Beauty Trends of 2023 (and Whether They’re Worth Trying

- 16 of the Best LED Masks in Australia and Exactly What Each Light Does for Your Skin